Nothing prepared us for this small Caribbean island, not our maps, not our omnipresent iPhones, not our best intentions. From the moment we arrived, everything assaulted us. The colors, vibrant; the people, guarded; the sun, brutal. We wanted an escape. Liberation from reality. A break from our cold, gray, gritty winter. The chance to turn bitter truths into lies.

We drove the twisted island roads, where we had to navigate by feel rather than sight. Carefully planned trips to dinner quickly dissolved into goose chases as restaurants eluded us. Nothing lasts on an island. By the end of our trip we’d sampled a wide variety of island cuisines, from simple pinchos by the road the first night to tacos on a bluff overlooking the rainforest to empanadas and croquettas in a café on a busy square. The unpredictability riled us.

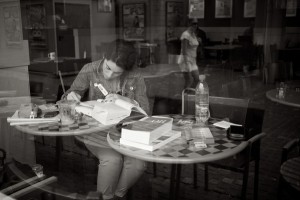

In our wanderings, we found fences. Fences edged even the most run down homes, staking off territory, setting boundaries as if the island itself weren’t solitary enough, as if this spot of land could ever be owned. Barbed wire fences lined the glimmering beaches, grates locked up the defunct restaurants, blocking access. We respected our limits. We did small things – hiked to a stone tower, stumbled our way into a cave, ferried to a tiny island with a strip of brown sugar sand. We found an old church, its joyful music pouring through its wrought-iron grates. In the old city we found a few more places where life escaped the fences – rounding a street corner we came to a window without a pane, a woman just inside sitting at her kitchen table. We said hello.

Who could we be here? Certainly not who we thought we were. The island had its own ideas, its inhabitants, others. The island tried to darken our skin and lighten our hair; it tried to change us. Its inhabitants spoke to us only in English, refusing to teach us. The island initiated us, its inhabitants imitated us.

Our old ways failed us. You, driving, always chose the wrong fork, and I, frantic, would cry out, “Stop!†and then, “Turn left. Here.†And despite your irritation, we found that this new way, this irrational and immediate method of judgment-making, worked. We went in-between. We were forced to stumble, jerk, grope, seep, abandon our desires in favor of finding the surprises. So maybe this will be our new thing.