My sister’s been dead to me for years, but last fall she decided to finally make it official. Funny, it wasn’t the decades of abusing crack and heroin that did her in after all. She slipped in the shower, broke her ribs, and came down with pneumonia in the hospital. (Like mother, like daughter, if you know the story.)

I was ready for the call; hell, I waited for it for, what — 23 years. Still, it hurt to hear my sweet niece tell me that her mom had died. The funeral was outside, graveside, underneath gnarled trees shedding fiery leaves on a glimmering fall day. It was painfully beautiful. There was a rabbi, a gaggle of old relatives, and a surprising number of more recent friends. My niece, Sarah, and her fiancé, Dan. Kim’s third child, Zack, with his adoptive family. An old black guy who sat in front, pouring his eyes out. Me, Geoff, and the kids, wide-eyed to be at their first funeral, for an aunt they barely even knew they had. A fresh hole in the family plot and a coffin on rollers.

Kim’s cousin Randi did the eulogy. She called me Chrissy. She talked about growing up with Kim in Baltimore, about the art projects she and Kim used to do with my mom. About sleepovers at their bubbie’s house, when Kim taught her to French kiss using pillows. She made us laugh, which I didn’t expect to do.

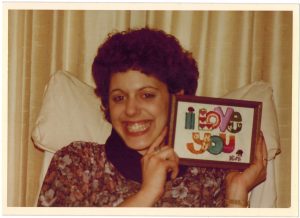

If I had done the eulogy, I’d have probably told the story of how Kim pierced my ears with a sewing needle when I was nine, overtop of her kitchen sink. I would have told how she dyed my hair blonde when I was eleven, and how it took me two agonizing years to grow it out. She was the one who taught me to shave my legs, the one who’d come get me for sister time and take me shmying at the secondhand shops, the one who’d ask me about my crushes, the one who’d always encourage me to be bold. I would have reflected on the good bits – how probably more than anyone else in my life before or since, Kim taught me to experiment with this life of mine. To try and see.

I know I’ve mentioned it before, but I would have talked about how heartbroken I was at sixteen, the day Kim came to tell my mom and me that she had just done heroin with her new boyfriend. The day we begged her to stay, but she left anyway. Forever. I wouldn’t have lied, like her cousin Randi did, and said that Kim was a good mom. She wasn’t. She bailed, to gradually worsening degrees, on all four of her kids. On all of us. Including herself.

I’m glad that I didn’t do the eulogy. I needed time to let myself feel, and it took me awhile. Now that I’ve had a few months, I’d like to go back and visit Kim’s grave. I’d talk to her, let her know that I’m glad to finally know where she is after all these years. I’d tell her I’m sorry that I shut her out. I’d tell her I wish we’d had the chance to turn things around while she was alive. I’d tell her I’ve missed her all this time. That I forgive her. That I love her still, despite everything.