Edit me.

I can’t exactly explain how this concept came to me. You’ll have to content yourself with the knowledge that it arose from deep within my subconscious.

I will admit that I’m drawn to the way “edit me” sounds vaguely dirty, sexual. It’s true, right?

Why the mixture of languages? Why edit moi? It opens the toolbox of language(s). It complicates, it captures a certain sense of everythingness. It includes. Mixing fights the limits of language.

Last week, a friend shared a post from this blog, coincidentally on the same subject. The blogger is quite religious, and on those grounds he rejects the necessity of editing himself. I’d describe him as radically self-acceptant and I’d lie if I told you that I wasn’t envious. But I just don’t have that much certainty in any single religion.

For me, editing is a process. For those of you who don’t know me or have never read my resume, I worked as an editor for a number of years. The company I worked for is old and venerated. I learned from the best. I know what I’m talking about when it comes to editing.

The editor takes the raw material and corrects it of course, but she does more than that. She shapes the narrative, ensuring that each concept flows logically to the next. She knows roughly what she wants to produce, and she teases the writing to create that reality. She is a gatekeeper to understanding, pushing the limits of language to guide the reader on the path that she has chosen for him.

So what do I mean by “edit me,” and how can a blog accomplish this? A few months ago, I confided in some friends about my recent inner turmoil. One commented, startlingly, “You always seem so perfect.”

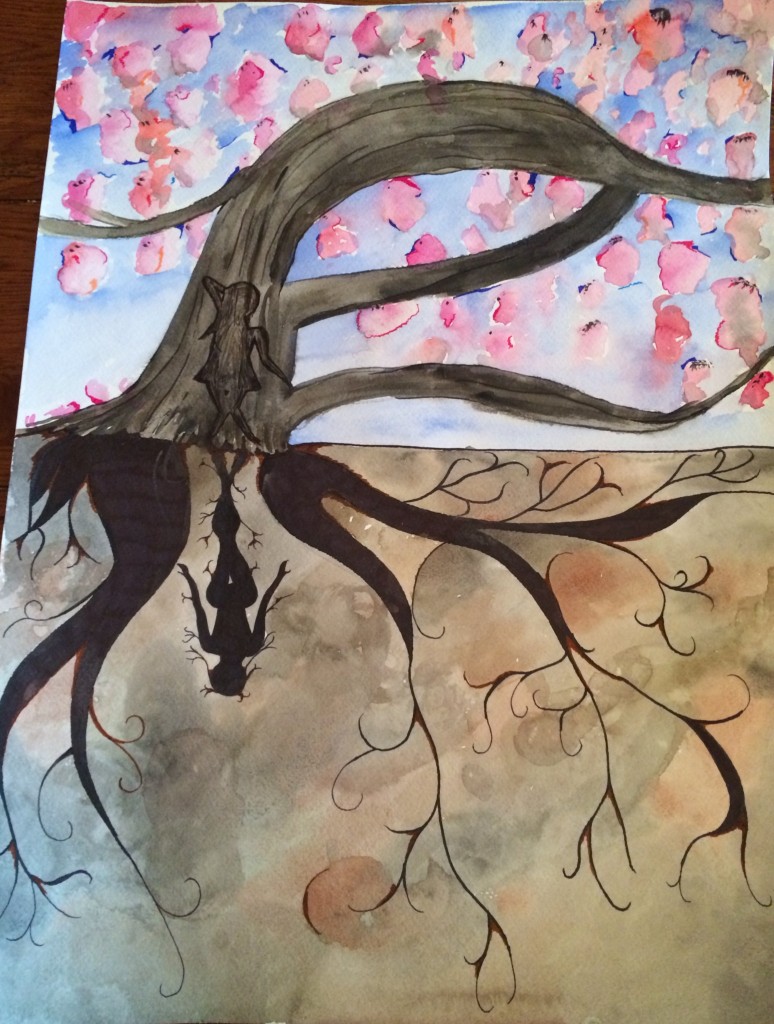

I’m not perfect. But I’ve so carefully created a singular version of myself — in opposition to my father, my sister, my aunt, my grandmother (people I’ve written about and will write of). This version is incomplete. Yet if you glance at the facts of my life as I usually present them, that glimmer of perfection shows.

This presents me with many difficulties. It’s hard to hide so much about myself. It goes against my open nature. To preserve the singular version of perfection, I’ve denied myself a lot of fun. I’ve never allowed myself to mess up, to break the rules. And what of those hidden truths? I’ve realized that hiding parts of myself, or locking out people I love, only redoubles their power over me.

Everyone needs an editor. It’s a job that you cannot accomplish on your own, even on paper. An editor must bring an objective eye to the writing, to the material, and no one has that much self-awareness.

So, edit me. I’ve gotten it right, but believe me, I’ve also gotten it wrong. I want to put some of the parts back in. I want to mix up my narrative and see what that creates. I want to reconnect with what I’ve denied about myself and my history.

I need help. If you’re reading this, maybe you know a thing or two about what I’m saying. Maybe you see things differently. I’d like to hear your thoughts. Don’t worry that you’ll hurt me. This is a collaboration. I’ll fill you in on the cast of characters, the settings, the plot twists and turns. Then I hope that you’ll chime in. I’d like to hear similar stories and opposite stories. I want to find the cracks in my narrative and tear them open to see what’s inside. It will be productive for me.

So, come on, edit me.